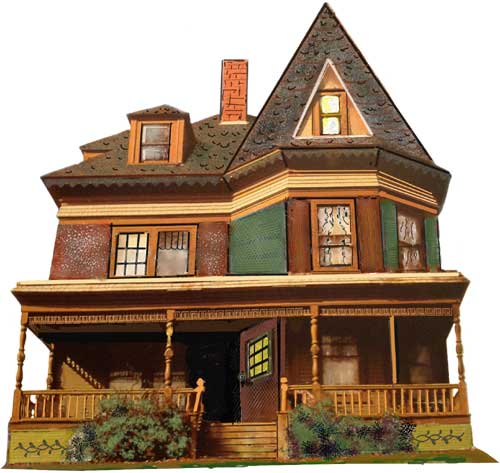

The Halloween HouseWritten and Illustrated by Carol MooreInspired by and dedicated to John D. Barrett, Jr., Esq. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Halloween House is big and old. I'm told that on Halloween night things happen there. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Now Suzie's moved in--she's only 4--along with her brother, her

father and mother, and little Picador. He's their dog. Well, maybe half

a dog. He's a Chihuahua, as small as they come. Suzie's room is in the attic. It's no fun. With a high ceiling, cold and gloomy, and shadows that run halfway up the walls. Suzie hides under the blanket. Picador too. Come on, he's no guard dog. Suzie's mom bought her a bear. A teddy bear named Teddy. He's big and fluffy and Suzie adores him. "I love you so much" she says. Then she wraps her arms around him, snuggling like a cat ready to purr while Picador buries himself in all that fur. The Halloween House's attic may be scary, but Teddy's not. Around his neck he wears a blue scarf with red polka dots. On his back paws are black tennis shoes tied with lace and plenty of knots. Something is silly about that teddy bear. He's got a goofy smile from ear to ear. It's kind of lopsided and sweet, although not quite complete. He was cheap when Suzie's mom bought him at the Dollar Store. But his smile is always there. When scratching and squeaking come from the walls,

Teddy smiles.

When clothes on the floor become strange figures in piles,

Teddy smiles.

When an invisible spider's miles of cobweb fades away in the morning,

Teddy smiles.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Friday, 29 November 2013

The Halloween House

A Song of Joys by Walt Whitman

A Song of Joys By "Walt Whitman"

O to make the most jubilant song!

Full of music full of manhood, womanhood, infancy!

Full of common employments full of grain and trees.

Full of music full of manhood, womanhood, infancy!

Full of common employments full of grain and trees.

O for the voices of animals O

for the swiftness and balance of fishes!

O for the dropping of raindrops in a song!

O for the sunshine and motion of waves in a song!

O for the dropping of raindrops in a song!

O for the sunshine and motion of waves in a song!

O the joy of my spirit it is

uncaged it darts like lightning!

It is not enough to have this globe or a certain time,

I will have thousands of globes and all time.

It is not enough to have this globe or a certain time,

I will have thousands of globes and all time.

O the engineer’s joys! to go with

a locomotive!

To hear the hiss of steam, the merry shriek, the steam-whistle, the

laughing locomotive!

To push with resistless way and speed off in the distance.

To hear the hiss of steam, the merry shriek, the steam-whistle, the

laughing locomotive!

To push with resistless way and speed off in the distance.

O the gleesome saunter over fields and

hillsides!

The leaves and flowers of the commonest weeds, the moist fresh

stillness of the woods,

The exquisite smell of the earth at daybreak, and all through the forenoon.

The leaves and flowers of the commonest weeds, the moist fresh

stillness of the woods,

The exquisite smell of the earth at daybreak, and all through the forenoon.

O the horseman’s and horsewoman’s

joys!

The saddle, the gallop, the pressure upon the seat, the cool

gurgling by the ears and hair.

The saddle, the gallop, the pressure upon the seat, the cool

gurgling by the ears and hair.

O the fireman’s joys!

I hear the alarm at dead of night,

I hear bells, shouts! I pass the crowd, I run!

The sight of the flames maddens me with pleasure.

I hear the alarm at dead of night,

I hear bells, shouts! I pass the crowd, I run!

The sight of the flames maddens me with pleasure.

O the joy of the strong-brawn’d

fighter, towering in the arena in

perfect condition, conscious of power, thirsting to meet his opponent.

perfect condition, conscious of power, thirsting to meet his opponent.

O the joy of that vast elemental sympathy

which only the human soul is

capable of generating and emitting in steady and limitless floods.

capable of generating and emitting in steady and limitless floods.

O the mother’s joys!

The watching, the endurance, the precious love, the anguish, the

patiently yielded life.

The watching, the endurance, the precious love, the anguish, the

patiently yielded life.

O the of increase, growth, recuperation,

The joy of soothing and pacifying, the joy of concord and harmony.

The joy of soothing and pacifying, the joy of concord and harmony.

O to go back to the place where I was

born,

To hear the birds sing once more,

To ramble about the house and barn and over the fields once more,

And through the orchard and along the old lanes once more.

To hear the birds sing once more,

To ramble about the house and barn and over the fields once more,

And through the orchard and along the old lanes once more.

O to have been brought up on bays, lagoons,

creeks, or along the coast,

To continue and be employ’d there all my life,

The briny and damp smell, the shore, the salt weeds exposed at low water,

The work of fishermen, the work of the eel-fisher and clam-fisher;

I come with my clam-rake and spade, I come with my eel-spear,

Is the tide out? I Join the group of clam-diggers on the flats,

I laugh and work with them, I joke at my work like a mettlesome young man;

In winter I take my eel-basket and eel-spear and travel out on foot

on the ice I have a small axe to cut holes in the ice,

Behold me well-clothed going gayly or returning in the afternoon,

my brood of tough boys accompanying me,

My brood of grown and part-grown boys, who love to be with no

one else so well as they love to be with me,

By day to work with me, and by night to sleep with me.

To continue and be employ’d there all my life,

The briny and damp smell, the shore, the salt weeds exposed at low water,

The work of fishermen, the work of the eel-fisher and clam-fisher;

I come with my clam-rake and spade, I come with my eel-spear,

Is the tide out? I Join the group of clam-diggers on the flats,

I laugh and work with them, I joke at my work like a mettlesome young man;

In winter I take my eel-basket and eel-spear and travel out on foot

on the ice I have a small axe to cut holes in the ice,

Behold me well-clothed going gayly or returning in the afternoon,

my brood of tough boys accompanying me,

My brood of grown and part-grown boys, who love to be with no

one else so well as they love to be with me,

By day to work with me, and by night to sleep with me.

Another time in warm weather out in a

boat, to lift the lobster-pots

where they are sunk with heavy stones, (I know the buoys,)

O the sweetness of the Fifth-month morning upon the water as I row

just before sunrise toward the buoys,

I pull the wicker pots up slantingly, the dark green lobsters are

desperate with their claws as I take them out, I insert

wooden pegs in the ’oints of their pincers,

where they are sunk with heavy stones, (I know the buoys,)

O the sweetness of the Fifth-month morning upon the water as I row

just before sunrise toward the buoys,

I pull the wicker pots up slantingly, the dark green lobsters are

desperate with their claws as I take them out, I insert

wooden pegs in the ’oints of their pincers,

I go to all the places one after another,

and then row back to the shore,

There in a huge kettle of boiling water the lobsters shall be boil’d

till their color becomes scarlet.

There in a huge kettle of boiling water the lobsters shall be boil’d

till their color becomes scarlet.

Another time mackerel-taking,

Voracious, mad for the hook, near the surface, they seem to fill the

water for miles;

Another time fishing for rock-fish in Chesapeake bay, I one of the

brown-faced crew;

Another time trailing for blue-fish off Paumanok, I stand with braced body,

My left foot is on the gunwale, my right arm throws far out the

coils of slender rope,

In sight around me the quick veering and darting of fifty skiffs, my

companions.

Voracious, mad for the hook, near the surface, they seem to fill the

water for miles;

Another time fishing for rock-fish in Chesapeake bay, I one of the

brown-faced crew;

Another time trailing for blue-fish off Paumanok, I stand with braced body,

My left foot is on the gunwale, my right arm throws far out the

coils of slender rope,

In sight around me the quick veering and darting of fifty skiffs, my

companions.

O boating on the rivers,

The voyage down the St. Lawrence, the superb scenery, the steamers,

The ships sailing, the Thousand Islands, the occasional timber-raft

and the raftsmen with long-reaching sweep-oars,

The little huts on the rafts, and the stream of smoke when they cook

supper at evening.

The voyage down the St. Lawrence, the superb scenery, the steamers,

The ships sailing, the Thousand Islands, the occasional timber-raft

and the raftsmen with long-reaching sweep-oars,

The little huts on the rafts, and the stream of smoke when they cook

supper at evening.

(O something pernicious and dread!

Something far away from a puny and pious life!

Something unproved! something in a trance!

Something escaped from the anchorage and driving free.)

Something far away from a puny and pious life!

Something unproved! something in a trance!

Something escaped from the anchorage and driving free.)

O to work in mines, or forging iron,

Foundry casting, the foundry itself, the rude high roof, the ample

and shadow’d space,

The furnace, the hot liquid pour’d out and running.

Foundry casting, the foundry itself, the rude high roof, the ample

and shadow’d space,

The furnace, the hot liquid pour’d out and running.

O to resume the joys of the soldier!

To feel the presence of a brave commanding officer to feel his sympathy!

To behold his calmness to be warm’d in the rays of his smile!

To go to battle to hear the bugles play and the drums beat!

To hear the crash of artillery to see the glittering of the bayonets

and musket-barrels in the sun!

To feel the presence of a brave commanding officer to feel his sympathy!

To behold his calmness to be warm’d in the rays of his smile!

To go to battle to hear the bugles play and the drums beat!

To hear the crash of artillery to see the glittering of the bayonets

and musket-barrels in the sun!

To see men fall and die and not complain!

To taste the savage taste of blood to be so devilish!

To gloat so over the wounds and deaths of the enemy.

To taste the savage taste of blood to be so devilish!

To gloat so over the wounds and deaths of the enemy.

O the whaleman’s joys! O I

cruise my old cruise again!

I feel the ship’s motion under me, I feel the Atlantic breezes fanning me,

I hear the cry again sent down from the mast-head, There she blows!

Again I spring up the rigging to look with the rest we descend,

wild with excitement,

I leap in the lower’d boat, we row toward our prey where he lies,

We approach stealthy and silent, I see the mountainous mass,

lethargic, basking,

I see the harpooneer standing up, I see the weapon dart from his

vigorous arm;

O swift again far out in the ocean the wounded whale, settling,

running to windward, tows me,

Again I see him rise to breathe, we row close again,

I see a lance driven through his side, press’d deep, turn’d in the wound,

Again we back off, I see him settle again, the life is leaving him fast,

As he rises he spouts blood, I see him swim in circles narrower and

narrower, swiftly cutting the water I see him die,

He gives one convulsive leap in the centre of the circle, and then

falls flat and still in the bloody foam.

I feel the ship’s motion under me, I feel the Atlantic breezes fanning me,

I hear the cry again sent down from the mast-head, There she blows!

Again I spring up the rigging to look with the rest we descend,

wild with excitement,

I leap in the lower’d boat, we row toward our prey where he lies,

We approach stealthy and silent, I see the mountainous mass,

lethargic, basking,

I see the harpooneer standing up, I see the weapon dart from his

vigorous arm;

O swift again far out in the ocean the wounded whale, settling,

running to windward, tows me,

Again I see him rise to breathe, we row close again,

I see a lance driven through his side, press’d deep, turn’d in the wound,

Again we back off, I see him settle again, the life is leaving him fast,

As he rises he spouts blood, I see him swim in circles narrower and

narrower, swiftly cutting the water I see him die,

He gives one convulsive leap in the centre of the circle, and then

falls flat and still in the bloody foam.

O the old manhood of me, my noblest joy

of all!

My children and grand-children, my white hair and beard,

My largeness, calmness, majesty, out of the long stretch of my life.

My children and grand-children, my white hair and beard,

My largeness, calmness, majesty, out of the long stretch of my life.

O ripen’d joy of womanhood!

O happiness at last!

I am more than eighty years of age, I am the most venerable mother,

How clear is my mind how all people draw nigh to me!

What attractions are these beyond any before? what bloom more

than the bloom of youth?

What beauty is this that descends upon me and rises out of me?

I am more than eighty years of age, I am the most venerable mother,

How clear is my mind how all people draw nigh to me!

What attractions are these beyond any before? what bloom more

than the bloom of youth?

What beauty is this that descends upon me and rises out of me?

O the orator’s joys!

To inflate the chest, to roll the thunder of the voice out from the

ribs and throat,

To make the people rage, weep, hate, desire, with yourself,

To lead America to quell America with a great tongue.

To inflate the chest, to roll the thunder of the voice out from the

ribs and throat,

To make the people rage, weep, hate, desire, with yourself,

To lead America to quell America with a great tongue.

O the joy of my soul leaning pois’d

on itself, receiving identity through

materials and loving them, observing characters and absorbing them,

My soul vibrated back to me from them, from sight, hearing, touch,

reason, articulation, comparison, memory, and the like,

The real life of my senses and flesh transcending my senses and flesh,

My body done with materials, my sight done with my material eyes,

Proved to me this day beyond cavil that it is not my material eyes

which finally see,

Nor my material body which finally loves, walks, laughs, shouts,

embraces, procreates.

materials and loving them, observing characters and absorbing them,

My soul vibrated back to me from them, from sight, hearing, touch,

reason, articulation, comparison, memory, and the like,

The real life of my senses and flesh transcending my senses and flesh,

My body done with materials, my sight done with my material eyes,

Proved to me this day beyond cavil that it is not my material eyes

which finally see,

Nor my material body which finally loves, walks, laughs, shouts,

embraces, procreates.

O the farmer’s joys!

Ohioan’s, Illinoisian’s, Wisconsinese’, Kanadian’s, Iowan’s,

Kansian’s, Missourian’s, Oregonese’ joys!

To rise at peep of day and pass forth nimbly to work,

To plough land in the fall for winter-sown crops,

To plough land in the spring for maize,

To train orchards, to graft the trees, to gather apples in the fall.

Ohioan’s, Illinoisian’s, Wisconsinese’, Kanadian’s, Iowan’s,

Kansian’s, Missourian’s, Oregonese’ joys!

To rise at peep of day and pass forth nimbly to work,

To plough land in the fall for winter-sown crops,

To plough land in the spring for maize,

To train orchards, to graft the trees, to gather apples in the fall.

O to bathe in the swimming-bath, or in

a good place along shore,

To splash the water! to walk ankle-deep, or race naked along the shore.

To splash the water! to walk ankle-deep, or race naked along the shore.

O to realize space!

The plenteousness of all, that there are no bounds,

To emerge and be of the sky, of the sun and moon and flying

clouds, as one with them.

The plenteousness of all, that there are no bounds,

To emerge and be of the sky, of the sun and moon and flying

clouds, as one with them.

O the joy a manly self-hood!

To be servile to none, to defer to none, not to any tyrant known or unknown,

To walk with erect carriage, a step springy and elastic,

To look with calm gaze or with a flashing eye,

To speak with a full and sonorous voice out of a broad chest,

To confront with your personality all the other personalities of the earth.

To be servile to none, to defer to none, not to any tyrant known or unknown,

To walk with erect carriage, a step springy and elastic,

To look with calm gaze or with a flashing eye,

To speak with a full and sonorous voice out of a broad chest,

To confront with your personality all the other personalities of the earth.

Knowist thou the excellent joys of youth?

Joys of the dear companions and of the merry word and laughing face?

Joy of the glad light-beaming day, joy of the wide-breath’d games?

Joy of sweet music, joy of the lighted ball-room and the dancers?

Joy of the plenteous dinner, strong carouse and drinking?

Joys of the dear companions and of the merry word and laughing face?

Joy of the glad light-beaming day, joy of the wide-breath’d games?

Joy of sweet music, joy of the lighted ball-room and the dancers?

Joy of the plenteous dinner, strong carouse and drinking?

Yet O my soul supreme!

Knowist thou the joys of pensive thought?

Joys of the free and lonesome heart, the tender, gloomy heart?

Joys of the solitary walk, the spirit bow’d yet proud, the suffering

and the struggle?

The agonistic throes, the ecstasies, joys of the solemn musings day

or night?

Joys of the thought of Death, the great spheres Time and Space?

Prophetic joys of better, loftier love’s ideals, the divine wife,

the sweet, eternal, perfect comrade?

Joys all thine own undying one, joys worthy thee O soul.

Knowist thou the joys of pensive thought?

Joys of the free and lonesome heart, the tender, gloomy heart?

Joys of the solitary walk, the spirit bow’d yet proud, the suffering

and the struggle?

The agonistic throes, the ecstasies, joys of the solemn musings day

or night?

Joys of the thought of Death, the great spheres Time and Space?

Prophetic joys of better, loftier love’s ideals, the divine wife,

the sweet, eternal, perfect comrade?

Joys all thine own undying one, joys worthy thee O soul.

O while I live to be the ruler of life,

not a slave,

To meet life as a powerful conqueror,

No fumes, no ennui, no more complaints or scornful criticisms,

To these proud laws of the air, the water and the ground, proving

my interior soul impregnable,

And nothing exterior shall ever take command of me.

To meet life as a powerful conqueror,

No fumes, no ennui, no more complaints or scornful criticisms,

To these proud laws of the air, the water and the ground, proving

my interior soul impregnable,

And nothing exterior shall ever take command of me.

For not life’s joys alone I sing,

repeating the joy of death!

The beautiful touch of Death, soothing and benumbing a few moments,

for reasons,

Myself discharging my excrementitious body to be burn’d, or render’d

to powder, or buried,

My real body doubtless left to me for other spheres,

My voided body nothing more to me, returning to the purifications,

further offices, eternal uses of the earth.

The beautiful touch of Death, soothing and benumbing a few moments,

for reasons,

Myself discharging my excrementitious body to be burn’d, or render’d

to powder, or buried,

My real body doubtless left to me for other spheres,

My voided body nothing more to me, returning to the purifications,

further offices, eternal uses of the earth.

O to attract by more than attraction!

How it is I know not yet behold! the something which obeys none

of the rest,

It is offensive, never defensive yet how magnetic it draws.

How it is I know not yet behold! the something which obeys none

of the rest,

It is offensive, never defensive yet how magnetic it draws.

O to struggle against great odds, to meet

enemies undaunted!

To be entirely alone with them, to find how much one can stand!

To look strife, torture, prison, popular odium, face to face!

To mount the scaffold, to advance to the muzzles of guns with

perfect nonchalance!

To be indeed a God!

To be entirely alone with them, to find how much one can stand!

To look strife, torture, prison, popular odium, face to face!

To mount the scaffold, to advance to the muzzles of guns with

perfect nonchalance!

To be indeed a God!

O to sail to sea in a ship!

To leave this steady unendurable land,

To leave the tiresome sameness of the streets, the sidewalks and the

houses,

To leave you O you solid motionless land, and entering a ship,

To sail and sail and sail!

To leave this steady unendurable land,

To leave the tiresome sameness of the streets, the sidewalks and the

houses,

To leave you O you solid motionless land, and entering a ship,

To sail and sail and sail!

O to have life henceforth a poem of new

joys!

To dance, clap hands, exult, shout, skip, leap, roll on, float on!

To be a sailor of the world bound for all ports,

A ship itself, (see indeed these sails I spread to the sun and air,)

A swift and swelling ship full of rich words, full of joys.

To dance, clap hands, exult, shout, skip, leap, roll on, float on!

To be a sailor of the world bound for all ports,

A ship itself, (see indeed these sails I spread to the sun and air,)

A swift and swelling ship full of rich words, full of joys.

Thursday, 28 November 2013

Anne of Green Gables

Anne of Green Gables

There are plenty of people in Avonlea and out of it, who can attend closely to their neighbor's business by dint of neglecting their own; but Mrs. Rachel Lynde was one of those capable creatures who can manage their own concerns and those of other folks into the bargain. She was a notable housewife; her work was always done and well done; she "ran" the Sewing Circle, helped run the Sunday-school, and was the strongest prop of the Church Aid Society and Foreign Missions Auxiliary. Yet with all this Mrs. Rachel found abundant time to sit for hours at her kitchen window, knitting "cotton warp" quilts--she had knitted sixteen of them, as Avonlea housekeepers were wont to tell in awed voices--and keeping a sharp eye on the main road that crossed the hollow and wound up the steep red hill beyond. Since Avonlea occupied a little triangular peninsula jutting out into the Gulf of St. Lawrence with water on two sides of it, anybody who went out of it or into it had to pass over that hill road and so run the unseen gauntlet of Mrs. Rachel's all-seeing eye.

She was sitting there one afternoon in early June. The sun was coming in at the window warm and bright; the orchard on the slope below the house was in a bridal flush of pinky- white bloom, hummed over by a myriad of bees. Thomas Lynde-- a meek little man whom Avonlea people called "Rachel Lynde's husband"--was sowing his late turnip seed on the hill field beyond the barn; and Matthew Cuthbert ought to have been sowing his on the big red brook field away over by Green Gables. Mrs. Rachel knew that he ought because she had heard him tell Peter Morrison the evening before in William J. Blair's store over at Carmody that he meant to sow his turnip seed the next afternoon. Peter had asked him, of course, for Matthew Cuthbert had never been known to volunteer information about anything in his whole life.

And yet here was Matthew Cuthbert, at half-past three on the afternoon of a busy day, placidly driving over the hollow and up the hill; moreover, he wore a white collar and his best suit of clothes, which was plain proof that he was going out of Avonlea; and he had the buggy and the sorrel mare, which betokened that he was going a considerable distance. Now, where was Matthew Cuthbert going and why was he going there?

Had it been any other man in Avonlea, Mrs. Rachel, deftly putting this and that together, might have given a pretty good guess as to both questions. But Matthew so rarely went from home that it must be something pressing and unusual which was taking him; he was the shyest man alive and hated to have to go among strangers or to any place where he might have to talk. Matthew, dressed up with a white collar and driving in a buggy, was something that didn't happen often. Mrs. Rachel, ponder as she might, could make nothing of it and her afternoon's enjoyment was spoiled.

"I'll just step over to Green Gables after tea and find out from Marilla where he's gone and why," the worthy woman finally concluded. "He doesn't generally go to town this time of year and he NEVER visits; if he'd run out of turnip seed he wouldn't dress up and take the buggy to go for more; he wasn't driving fast enough to be going for a doctor. Yet something must have happened since last night to start him off. I'm clean puzzled, that's what, and I won't know a minute's peace of mind or conscience until I know what has taken Matthew Cuthbert out of Avonlea today."

Accordingly after tea Mrs. Rachel set out; she had not far to go; the big, rambling, orchard-embowered house where the Cuthberts lived was a scant quarter of a mile up the road from Lynde's Hollow. To be sure, the long lane made it a good deal further. Matthew Cuthbert's father, as shy and silent as his son after him, had got as far away as he possibly could from his fellow men without actually retreating into the woods when he founded his homestead. Green Gables was built at the furthest edge of his cleared land and there it was to this day, barely visible from the main road along which all the other Avonlea houses were so sociably situated. Mrs. Rachel Lynde did not call living in such a place LIVING at all.

"It's just STAYING, that's what," she said as she stepped along the deep-rutted, grassy lane bordered with wild rose bushes. "It's no wonder Matthew and Marilla are both a little odd, living away back here by themselves. Trees aren't much company, though dear knows if they were t here'd be enough of them. I'd ruther look at people. To be sure, they seem contented enough; but then, I suppose, they're used to it. A body can get used to anything, even to being hanged, as the Irishman said."

With this Mrs. Rachel stepped out of the lane into the backyard of Green Gables. Very green and neat and precise was that yard, set about on one side with great patriarchal willows and the other with prim Lombardies. Not a stray stick nor stone was to be seen, for Mrs. Rachel would have seen it if there had been. Privately she was of the opinion that Marilla Cuthbert swept that yard over as often as she swept her house. One could have eaten a meal off the ground without overbrimming the proverbial peck of dirt.

Mrs. Rachel rapped smartly at the kitchen door and stepped in when bidden to do so. The kitchen at Green Gables was a cheerful apartment--or would have been cheerful if it had not been so painfully clean as to give it something of the appearance of an unused parlor. Its windows looked east and west; through the west one, looking out on the back yard, came a flood of mellow June sunlight; but the east one, whence you got a glimpse of the bloom white cherry-trees in the left orchard and nodding, slender birches down in the hollow by the brook, was greened over by a tangle of vines. Here sat Marilla Cuthbert, when she sat at all, always slightly distrustful of sunshine, which seemed to her too dancing and irresponsible a thing for a world which was meant to be taken seriously; and here she sat now, knitting, and the table behind her was laid for supper.

Mrs. Rachel, before she had fairly closed the door, had taken a mental note of everything that was on that table. There were three plates laid, so that Marilla must be expecting some one home with Matthew to tea; but the dishes were everyday dishes and there was only crab-apple preserves and on e kind of cake, so that the expected company could not be any particular company. Yet what of Matthew's white collar and the sorrel mare? Mrs. Rachel was getting fairly dizzy with this unusual mystery about quiet, unmysterious Green Gables.

"Good evening, Rachel," Marilla said briskly. "This is a real fine evening, isn't it" Won't you sit down? How are all your folks?"

Something that for lack of any other name might be called friendship existed and always had existed between Marilla Cuthbert and Mrs. Rachel, in spite of--or perhaps because of--their dissimilarity.

Marilla was a tall, thin woman, with angles and without curves; her dark hair showed some gray streaks and was always twisted up in a hard little knot behind with two wire hairpins stuck aggressively through it. She looked like a woman of narrow experience and rigid conscience, which she was; but there was a saving something about her mouth which, if it had been ever so slightly developed, might have been considered indicative of a sense of humor.

"We're all pretty well," said Mrs. Rachel. "I was kind of afraid YOU weren't, though, when I saw Matthew starting off today. I thought maybe he was going to the doctor's."

Marilla's lips twitched understandingly. She had expected Mrs. Rachel up; she had known that the sight of Matthew jaunting off so unaccountably would be too much for her neighbor's curiosity.

"Oh, no, I'm quite well although I had a bad headache yesterday," she said. "Mat thew went to Bright River. We're getting a little boy from an orphan asylum in Nova Scotia and he's coming on the train tonight."

If Marilla had said that Matthew had gone to Bright River to meet a kangaroo from Australia Mrs. Rachel could not have been more astonished. She was actually stricken dumb for five seconds. It was unsupposable that Marilla was making fun of her, but Mrs. Rachel was almost forced to suppose it.

"Are you in earnest, Marilla?" she demanded when voice returned to her.

"Yes, of course," said Marilla, as if getting boys from orphan asylums in Nova Scotia were part of the usual spring work on any well-regulated Avonlea farm instead of being an unheard of innovation.

Mrs. Rachel felt that she had received a severe mental jolt. She thought in exclamation points. A boy! Marilla and Matthew Cuthbert of all people adopting a boy! From an orphan asylum! Well, the world was certainly turning upside down! She would be surprised at nothing after this! Nothing!

"What on earth put such a notion into your head?" she demanded disapprovingly.

This had been done without here advice being asked, and must perforce be disapproved.

"Well, we've been thinking about it for some time--all winter in fact," returned Marilla. "Mrs. Alexander Spencer was up here one day before Christmas and she said she was going to get a little girl from the asylum over in Hopeton in the spring. Her cousin lives there and Mrs. Sp encer has visited here and knows all about it. So Matthew and I have talked it over off and on ever since. We thought we'd get a boy. Matthew is getting up in years, you know--he's sixty-- and he isn't so spry as he once was. His heart troubles him a good deal. And you know how desperate hard it's got to be to get hired help. There's never anybody to be had but those stupid, half-grown little French boys; and as soon as you do get one broke into your ways and taught something he's up and off to the lobster canneries or the States. At first Matthew suggested getting a Home boy. But I said `no' flat to that. `They may be all right--I'm not saying they're not--but no London street Arabs for me,' I said. `Give me a native born at least. There'll be a risk, no matter who we get. But I'll feel easier in my mind and sleep sounder at nights if we get a born Canadian.' So in the end we decided to ask Mrs. Spencer to pick us out one when she went over to get her little girl. We heard last week she was going, so we sent her word by Richard Spencer's folks at Carmody to bring us a smart, likely boy of about ten or eleven. We decided that would be the best age--old enough to be of some use in doing chores right off and young enough to be trained up proper. We mean to give him a good home and schooling. We had a telegram from Mrs. Alexander Spencer today--the mail-man brought it from the station-- saying they were coming on the five-thirty train tonight. So Matthew went to Bright River to meet him. Mrs. Spencer will drop him off there. Of course she goes on to White Sands station herself"

Mrs. Rachel prided herself on always speaking her mind; she proceeded to speak it now, having adjusted her mental attitude to this amazing piece of news.

"Well, Marilla, I'll just tell you plain that I think you're doing a mighty foolish thing--a risky thing, that's what. You don't know what you're getting. You're bringing a strange child into your house and home and you don't know a single thing about him nor what his disposition is like nor what sort of parents he had nor how he's likely to turn out. Why, it was only last week I read in the paper how a man and his wife up west of the Island took a boy out of an orphan asylum and he set fire to the house at night--set it ON PURPOSE, Marilla--and nearly burnt them to a crisp in their beds. And I know another case where an adopted boy used to suck the eggs--they couldn't break him of it. If you had asked my advice in the matter--which you didn't do, Marilla--I'd have said for mercy's sake not to think of such a thing, that's what."

This Job's comforting seemed neither to offend nor to alarm Marilla. She knitted steadily on.

"I don't deny there's something in what you say, Rachel. I've had some qualms myself. But Matthew was terrible set on it. I could see that, so I gave in. It's so seldom Matthew sets his mind on anything that when he does I always feel it's my duty to give in. And as for the risk, there's risks in pretty near everything a body does in this world. There's risks in people's having children of their own if it comes to that--they don't always turn out well. And then Nova Scotia is right close to the Island. It isn't as if we were getting him from England or the States. He can't be much different from ourselves."

"Well, I hope it will turn out all right," said Mrs. Rachel in a tone that plainly indicated her painful doubts. "Only don't say I didn't warn you if he burns Green Gables down or puts strychnine in the well--I heard of a case over in New Brunswick where an orphan asylum child di d that and the whole family died in fearful agonies. Only, it was a girl in that instance."

"Well, we're not getting a girl," said Marilla, as if poisoning wells were a purely feminine accomplishment and not to be dreaded in the case of a boy. "I'd never dream of taking a girl to bring up. I wonder at Mrs. Alexander Spencer for doing it. But there, SHE wouldn't shrink from adopting a whole orphan asylum if she took it into her head."

Mrs. Rachel would have liked to stay until Matthew came home with his imported orphan. But reflecting that it would be a good two hours at least before his arrival she concluded to go up the road to Robert Bell's and tell the news. It would certainly make a sensation second to none, and Mrs. Rachel dearly loved to make a sensation. So she took herself away, somewhat to Marilla's relief, for the latter felt her doubts and fears reviving under the influence of Mrs. Rachel's pessimism.

"Well, of all things that ever were or will be!" ejaculated Mrs. Rachel when she was safely out in the lane. "It does really seem as if I must be dreaming. Well, I'm sorry for that poor young one and no mistake. Matthew and Marilla don't know anything about children and they'll expect him to be wiser and steadier that his own grandfather, if so be's he ever had a grandfather, which is doubtful. It seems uncanny to think of a child at Green Gables somehow; there's never been one there, for Matthew and Marilla were grown up when the new house was built--if they ever WERE children, which is hard to believe when one looks at them. I wouldn't be in that orphan's shoes for anything. My, but I pity him, that's what."

So said Mrs. Rachel to the wild rose bushes out of the fulness of her

heart; but if she could have seen the child who was waiting patiently at

the Bright River station at that very moment her pity would have been

still deeper and more profound.

Monday, 25 November 2013

Mr Sticky

Mr Sticky

Mr Sticky

CJ Products

No one knew how Mr. Sticky got in the fish tank.

"He's very small," Mum said as she peered at the tiny water snail. "Just a black dot."

"He'll grow," said Abby and pulled her pyjama bottoms up again before she got into bed. They were always falling down.

In the morning Abby jumped out of bed and switched on the light in her fish tank.

Gerry, the fat orange goldfish, was dozing inside the stone archway. Jaws was already awake, swimming along the front of the tank with his white tail floating and twitching. It took Abby a while to find Mr. Sticky because he was clinging to the glass near the bottom, right next to the gravel.

At school that day she wrote about the mysterious Mr. Sticky who was so small you could mistake him for a piece of gravel. Some of the girls in her class said he seemed an ideal pet for her and kept giggling about it.

That night Abby turned on the light to find Mr. Sticky clinging to the very tiniest, waviest tip of the pond weed. It was near the water filter so he was bobbing about in the air bubbles.

"That looks fun," Abby said. She tried to imagine what it must be like to have to hang on to things all day and decided it was probably very tiring. She fed the fish then lay on her bed and watched them chase each other round and round the archway. When they stopped Gerry began nibbling at the pond weed with his big pouty lips. He sucked Mr. Sticky into his mouth then blew him back out again in a stream of water. The snail floated down to the bottom of the tank among the coloured gravel.

"I think he's grown a bit," Abby told her Mum at breakfast the next day.

"He's very small," Mum said as she peered at the tiny water snail. "Just a black dot."

"He'll grow," said Abby and pulled her pyjama bottoms up again before she got into bed. They were always falling down.

In the morning Abby jumped out of bed and switched on the light in her fish tank.

Gerry, the fat orange goldfish, was dozing inside the stone archway. Jaws was already awake, swimming along the front of the tank with his white tail floating and twitching. It took Abby a while to find Mr. Sticky because he was clinging to the glass near the bottom, right next to the gravel.

At school that day she wrote about the mysterious Mr. Sticky who was so small you could mistake him for a piece of gravel. Some of the girls in her class said he seemed an ideal pet for her and kept giggling about it.

That night Abby turned on the light to find Mr. Sticky clinging to the very tiniest, waviest tip of the pond weed. It was near the water filter so he was bobbing about in the air bubbles.

"That looks fun," Abby said. She tried to imagine what it must be like to have to hang on to things all day and decided it was probably very tiring. She fed the fish then lay on her bed and watched them chase each other round and round the archway. When they stopped Gerry began nibbling at the pond weed with his big pouty lips. He sucked Mr. Sticky into his mouth then blew him back out again in a stream of water. The snail floated down to the bottom of the tank among the coloured gravel.

"I think he's grown a bit," Abby told her Mum at breakfast the next day.

"Just as well if he's going to be gobbled up like that," her Mum said, trying to put on her coat and eat toast at the same time.

"But I don't want him to get too big or he won't be cute anymore. Small things are cute aren't they?"

"Yes they are. But big things can be cute too. Now hurry up, I'm going to miss my train."

At school that day, Abby drew an elephant. She needed two pieces of expensive paper to do both ends but the teacher didn't mind because she was pleased with the drawing and wanted it on the wall. They sellotaped them together, right across the elephant's middle. In the corner of the picture, Abby wrote her full name, Abigail, and drew tiny snails for the dots on the 'i's The teacher said that was very creative.

At the weekend they cleaned out the tank. "There's a lot of algae on the sides," Mum said. "I'm not sure Mr. Sticky's quite up to the job yet."

They scooped the fish out and put them in a bowl while they emptied some of the water. Mr. Sticky stayed out of the way, clinging to the glass while Mum used the special 'vacuum cleaner' to clean the gravel. Abby trimmed the new pieces of pond weed down to size and scrubbed the archway and the filter tube. Mum poured new water into the tank.

"Where's Mr. Sticky?" Abby asked.

"On the side," Mum said. She was busy concentrating on the water. "Don't worry I was careful."

Abby looked on all sides of the tank. There was no sign of the water snail.

"He's probably in the gravel then," her mum said. "Come on let's get this finished. I've got work to do." She plopped the fish back in the clean water where they swam round and round, looking puzzled.

That evening Abby went up to her bedroom to check the tank. The water had settled and looked lovely and clear but there was no sign of Mr. Sticky. She lay on her bed and did some exercises, stretching out her legs and feet and pointing her toes. Stretching was good for your muscles and made you look tall a model had said on the t.v. and she looked enormous. When Abby had finished, she kneeled down to have another look in the tank but there was still no sign of Mr. Sticky. She went downstairs.

Her mum was in the study surrounded by papers. She had her glasses on and her hair was all over the place where she'd been running her hands through it. She looked impatient when she saw Abby in the doorway and even more impatient when she heard the bad news.

"He'll turn up." was all she said. "Now off to bed Abby. I've got masses of work to catch up on."

Abby felt her face go hot and red. It always happened when she was angry or upset.

"You've hoovered him up haven't you," she said. You were in such a rush you hoovered him up."

"I have not. I was very careful. But he is extremely small."

"What's wrong with being small?"

"Nothing at all. But it makes things hard to find."

"Or notice," Abby said and ran from the room.

The door to the bedroom opened and Mum's face appeared around the crack. Abby tried to ignore her but it was hard when she walked over to the bed and sat next to her. She was holding her glasses in her hand. She waved them at Abby.

"These are my new pair," she said. "Extra powerful, for snail hunting." She smiled at Abby. Abby tried not to smile back.

< 4 >

"And I've got a magnifying glass," Abby suddenly remembered and rushed off to find it.

They sat beside each other on the floor. On their knees they shuffled around the tank, peering into the corners among the big pebbles, at the gravel and the pondweed.

"Ah ha!" Mum suddenly cried.

"What?" Abby moved her magnifying glass to where her mum was pointing.

There, tucked in the curve of the archway, perfectly hidden against the dark stone, sat Mr. Sticky. And right next to him was another water snail, even smaller than him.

"Mrs Sticky!" Abby breathed. "But where did she come from?"

"I'm beginning to suspect the pond weed don't you think?"

They both laughed and climbed into Abby's bed together, cuddling down under the duvet. It was cozy but a bit of a squeeze.

"Budge up," Mum said, giving Abby a push with her bottom.

"I can't, I'm already on the edge."

"My goodness you've grown then. When did that happen? You could have put an elephant in here last time we did this."

Abby put her head on her mum's chest and smiled.

Goodnight

Goodnight

|

|||

By Amanda

|

|||

| * |

Sweet dreams, Sleep tight, Have a good dream tonight, Move away from the day, Relax and don't delay, Fly away to dream land, To a nice peacful place, Goodnight. |

|

* |

The End

CJ Products | |||

Miri and the Gardener

Miri and the Gardener

| |||

| |

| ||

| | |||

Miri loves that tree with the many cavities sculpted with art

and dedication. But with the respect for the survival of the living tree, of course. Miri loves that tree with the many cavities sculpted with art

and dedication. But with the respect for the survival of the living tree, of course.  The problem is that poor Miri is suffering from a

mysterious illness. The magician healer was very upset. He had never encountered any such

sickness before. He searched the memory books left by previous magician-healers to no

avail unfortunately. The problem is that poor Miri is suffering from a

mysterious illness. The magician healer was very upset. He had never encountered any such

sickness before. He searched the memory books left by previous magician-healers to no

avail unfortunately. The little fairy, courageously continued to believe, in

spite of her suffering, that she would heal. Winter was long for little Miri who, from her

bed entertained her friends. She could not stand sorrow so she kept her morale up. With

spring came a hope, as fragile as the eggs in the nest. The little fairy, courageously continued to believe, in

spite of her suffering, that she would heal. Winter was long for little Miri who, from her

bed entertained her friends. She could not stand sorrow so she kept her morale up. With

spring came a hope, as fragile as the eggs in the nest.  The healer had discovered a cure. But it was the powder

that rests on the wings of butterflies. Hundreds maybe even thousands of butterflies,would

be needed to harvest sufficient quantities for the medicine for Miri. Miri’s father

was at the inn with his friend. He was discussing the problem of which no one seemed to

know the solution. It was a sad day for Miri’s father. The healer had discovered a cure. But it was the powder

that rests on the wings of butterflies. Hundreds maybe even thousands of butterflies,would

be needed to harvest sufficient quantities for the medicine for Miri. Miri’s father

was at the inn with his friend. He was discussing the problem of which no one seemed to

know the solution. It was a sad day for Miri’s father.  A stranger seated at a neighboring table, approached them

discreetly as the custom prescribes. He told Miri’s father; ”I think I can help

heal your daughter”. A stranger seated at a neighboring table, approached them

discreetly as the custom prescribes. He told Miri’s father; ”I think I can help

heal your daughter”. “Stranger, if you can accomplish that, I’ll give you everything you want” “I have no need for everything, all I need is work.” “Are you a healer?” “No a gardener, if you hire me I guarantee that your daughter will be healed by the end of summer." The honest tone and truthful gaze in the eyes of the gardener convinced Miri’s father to give him a chance. He had nothing to loose and Miri all to win... From her window, Miri looked at the gardener work, an old man with the precise movements acquired along a lifetime dedicated to the love of plants. The gardener planted lilac trees in many shades. He even planted unknown plants, bushes and flowers with strange, mysterious names that brings visions of exotic places. The old man told Miri that soon, he assured her, it would translate into a symphony of colors and textures that will perfume the air. He had such a pleasurable expression as he said it, that Miri was certain “HE” could smell it already. Miri observed as the young sprout escaped the soil, as the tender green shoots grew. Soon flower buds appeared followed by the most beautiful blooms.  The gossipers were having a good time. “Shameful, he

buys himself a garden while his daughter, poor girl, lay sick and all. Shameful, I tell

you.” The gossipers were having a good time. “Shameful, he

buys himself a garden while his daughter, poor girl, lay sick and all. Shameful, I tell

you.”  Then one warm day, attracted by the selected flowers

butterflies came, more and more of them kept coming to invade the garden. The gardener

installed a lawn chairs in the clearing and installed Miri comfortably in it. Then one warm day, attracted by the selected flowers

butterflies came, more and more of them kept coming to invade the garden. The gardener

installed a lawn chairs in the clearing and installed Miri comfortably in it. Miri received a shower of the powder falling from the wings of the butterflies. The powder was of many colors shining in the sun. The rays of the sun reflected in the fine powder.  The clearing was bathed in the light and in that light

Miri’s healing… In a week Miri was cured. Her delicate wings shone brightly

again. Her face had regained her healthy colors and above all her smile was resplendent. The clearing was bathed in the light and in that light

Miri’s healing… In a week Miri was cured. Her delicate wings shone brightly

again. Her face had regained her healthy colors and above all her smile was resplendent. And this is how Miri got her name: “MIRI THE BUTTERFLY FAIRY” | |||

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)